Oct 2–31, 2018

(free and open to the public)

Photo documentation→

The Absent Museum: Blueprint for a Museum of Contemporary Art for the Capital of Europe was published in 2017 on the occasion of an exhibition marking the 10th anniversary of WIELS, a contemporary arts center in Brussels. As a kunsthalle (an institution without a permanent collection), WIELS was founded with the challenge and opportunity to be in dialogue with the regional community of Brussels and the international audience beyond Europe’s capital. How can an arts center speak with constituents from a range of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds and how can those constituents find something at stake in what a new institution like WIELS says? Within the context of institutional narratives introduced in this issue of CRB Dispatch, we are drawn to essays and documentation of artworks in The Absent Museum and their investigations of how an institution behaves and speaks with audiences.

In his essay The Absent [Museum] the curator and writer Charles Esche reflects upon the museum as a socially-engaged institution. Esche is the director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, The Netherlands. Since his appointment in 2004, he has used the museum’s collection—primarily developed from a modernist, Western-centric focus—as a point of critical inquiry. He believes, “By looking at objects and relationships within the museum as elements within a history; as keys to unlock memory; and as traditions to be broken and/or upheld—we get closer to how the collections might be deployed precisely in the interests of wresting them away from the conformism that threatens to neutralize their potential.” [1] He continues by outlining how the Van Abbemuseum has identified ways to “put to use” the modernist era within a twenty-first century global context. Interpretations of collections can be shaped by audience. As the social demographics of Europe change with the influx of people from non-Western parts of the world, the relevance of a museum collection or an exhibition program change to reflect the audience, which could eventually become the community. Therefore, by leaving behind the constructed narrative of modernity, “its universal claim to a single truth, its patriarchy, its white privilege, its refusal to recognize other forms of knowledge, and its destructive occupation of others’ territories,” the museum can tell different stories. [2]

I recall an especially outstanding project called “Picasso in Palestine” organized by the Van Abbemuseum in 2011. For this project Esche and his team at the museum worked with the Ramallah-based artist and curator Khaled Hourani to orchestrate the loan of a painting by Picasso. They collaborated with the International Art Academy Palestine to make arrangements to lend and transport the Van Abbemuseum’s Buste de Femme (1943), the first time a Picasso had been exhibited in Palestine. The administrative hurdles involved with the loan were integral to the Van Abbemuseum’s mission to rethink the role of the collection, specifically how lending a painting by arguably the most famous artist in the world to Palestine would create a new narrative about the object, inserting it into a global conversation of politics and nation state. The discourse around the painting is now imbued with this recent action; the painting means something different to audiences.

Manuel Borja-Villel is the director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. Like Esche, he believes arts and cultural institutions have the capacity to rewrite static narratives that determine and influence a sense of culture and place. In his essay “Towards a Museum of the Common,” Borja-Villel says that an institution is responsible for communicating two ways, and that a story unfolds thanks to the audience. He argues that museums and art centers have lost the authority to mediate and define culture. New models are needed in face of constant cultural production and widespread distribution of images and ideas affecting how people interpret, understand and engage with the world. Borja-Villel sees the museum collection—the archive—as an opportunity for a common archive to spread, move, change and develop from the stories of shared experiences and memories, communicated and told by communities, near and far.

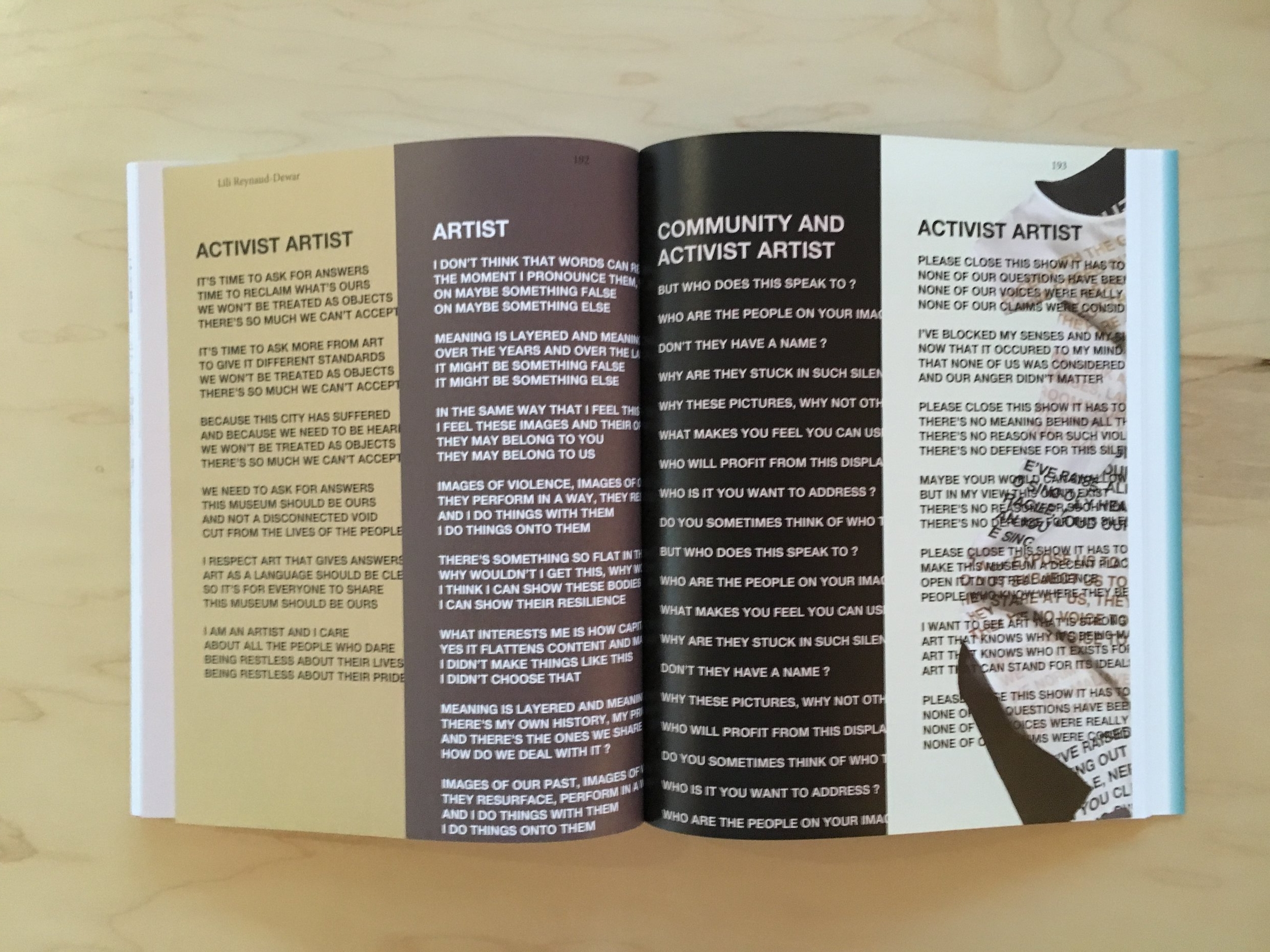

While Esche and Borja-Villel write about the museum collection, the French artist Lili Reynaud-Dewar wrote a libretto titled Small Tragic Opera of Images and Bodies in the Museum, which was performed as part of the exhibition. Reynaud-Dewar’s lyrics are reproduced in the The Absent Museum, along with graphic text panels relaying the titles and lyrics of characters—“Museum Staff,” “Curator,” “Community,” “Art Critic,” “Activist Artist,” and so on—originally printed on sac-like smocks worn over the bodies of the performers. Readers will discover the text panels, operatic performance and lyrics pose important questions about the role and responsibility of artists who work with and circulate archival images of trauma. Small Tragic Opera is an exposition of the various voices of an institution—both within and outside its walls—who have a say in the content, along with the changing role collections and archives play in interpreting recent events. The polemical text and performance causes one to think about the complex role of artists and institutions when they attempt to speak for others. The work reinforces the thesis of The Absent Museum: dialogue is paramount—whether with existing collections or temporary exhibitions and commissioned artworks. The art institution is a site conversation, a reciprocal exchange that has the potential to communicate with audiences and transform them into communities.

All of this returns us to questions related to audience and community at the CRB. A collection is content. Exhibitions and programs are content. Book inventory is content. A developing institution like the CRB speaks about a number of topics and is therefore responsible for a lot of content. We want to ensure that not only are audiences listening, but we have dialogue with them. The Absent Museum and the topic of “Audience” is the second in a series of displays using the inventory of the CRB bookshop as a launching point for assembling focused exhibitions. It led us to a selection of eight additional titles, some of which can be immensely valuable for sorting through these questions.

[1] Charles Esche, “The Absent [Museum],” The Absent Museum: Blueprint for a Museum of Contemporary Art for the Capital of Europe. Edited by Dirk Snauwaert (Brussels: WIELS, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017): 10.

[2] Esche, “The Absent [Museum],” 12.